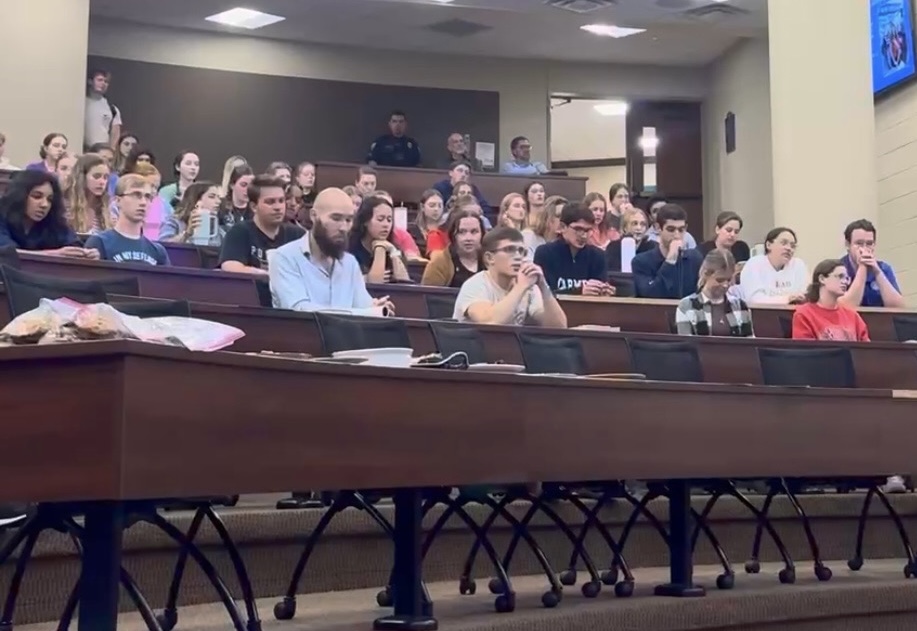

Susan Traffas, professor, co-chair for the honors program at Benedictine College, and director of the Great Books program, gave a final lecture to celebrate her retirement at the McCallister Boardroom in the Ferrell Academic Building this evening.

Her lecture was titled “The Charm of Competence, Revisited: The Liberal Arts vs. the Social Sciences”. It focused on how great books helped her with her former career in D.C., taking a focus on child welfare policy.

“The child welfare profession is predicated among the two interconnected planes of modernity,” Traffas said. “The omnipotence of science and the infinite malleability of man.”

Traffas continues to explain how the child welfare system is set up to improve the human condition. This is done through direct intervention at one of the smallest community levels: family.

“Mirroring the science of modern medicine, child welfare professionals are trained to look at human behavior as a doctor would look at disease,” Traffas said. “Just as doctors strive to eradicate cancer, child welfare professionals work to end all strife within family.”

Traffas goes on to say that the tools that child welfare professionals use are even similar to what you would use in the medical field. If someone abuses a child, they are in need of treatment. The case workers in the field use risk assessments to help with deciding whether a child needs to be removed from a home for their own safety.

“As if, by the use of a checklist, you can discern if someone is going to choose to do evil,” Traffas said. “Such tools lessen the dignity of all involved. They fail to take into account, in fact, attempt to replace the freewill of the parent and the judgment of the caseworker.”

Traffas explains that this causes the natural family to be replaced by social engineering, and that the process of child welfare case workers entering a home is done like a private matter. There is no due process for the parents and no warrant is needed.

“That we decide to intervene in cases of child abuse and neglect is not a problem,” Traffas said. Rather it is the manner of how that intervention is carried out.”

Nowadays, the way that society is changing to a more therapeutic state has heavily impacted how the child welfare profession accesses homes. Traffas explains how they are losing sight of looking at how to treat the malnourished soul of the parents. As well as how the changes within society are causing us to look at the structure of the family, concerning how that structure should function, in a different way.

Traffas shares a passage from G.K. Chesterton in What’s Wrong with the World.

“In most cases of family joys and sorrows, the state has no mood of entry. It is not so much so that the law should not interfere. It’s that the law cannot,” Chesterton wrote. “Creatures so close to each other, as husband and wife or as mother and children, have powers of making each other happy or miserable of which no public notion can heal. A child must depend on the most imperfect mother. The mother may be devoted to the most unworthy children.

In such relations, legal revenges are vain. Even in the abnormal cases where the law may operate, this difficulty is constantly found. The state has not the tools vallencant enough to dehalcynate the rooted habits and tangle the functions of family. The two sexes, whether happy or unhappy, are sown together too tightly for us to get the blade of a legal penknife between them.”

Traffas states how the modern therapeutic state of the system is made up of what Chesterton warns us against. She brings up how this can damage how we live a free life, because learning freedom starts within the family.

“The capacity for liberty must be nourished,” Traffas said. “We first learn how to be free within the confines of family life. We grow to self mastery as we gain control over our daily life.”

This starts by having control within one’s own household. However, the therapeutic side would have this turned over to the professionals. This undermines the capacity for liberty that Traffas states must be nourished in the family.

“Children abused by their parents’ hands deserve more than what the therapeutic state can give them,” Traffas said. “They deserve to be treated justly.”

The end of Traffas’ lecture was met with a roaring applause and standing ovation.

Dinner and speeches from staff members, current and former students, and her husband followed as well as a musical tribute. The list goes as follows: Andrew Salzmann, Renee Lataif, Cat Rea, Meraiah Martinez, Purtills, Tis Westhoff, Anne McKenna, Jamie Spiering, Alex Gorman, Catherine Francois, John Traffas, and Edward Mulholland.

Traffas plans to move closer to her children and grandchildren in retirement.